Overview

Polio is a crippling and potentially fatal infectious disease. There is no cure, but there are safe and effective vaccines, which given multiple times can protect a child for life. Eradicating polio requires immunizing every child until transmission stops and the world is free of all forms of poliovirus.

In 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) - of which WHO is a founding member – set out to eradicate polio all over the world. The mission required mass vaccination, reaching every child. At that stage, it was estimated that 350,000 children around the world were paralyzed by polio each year.

In the African Region, tremendous progress has been made in polio eradication over the last decades. The region’s geographic size, cultural diversity and logistical challenge, not to mention insecurity, displacement and pockets of vaccine refusal have shaped Africa’s polio response, driving innovative solutions to reaching all children with the vaccine.

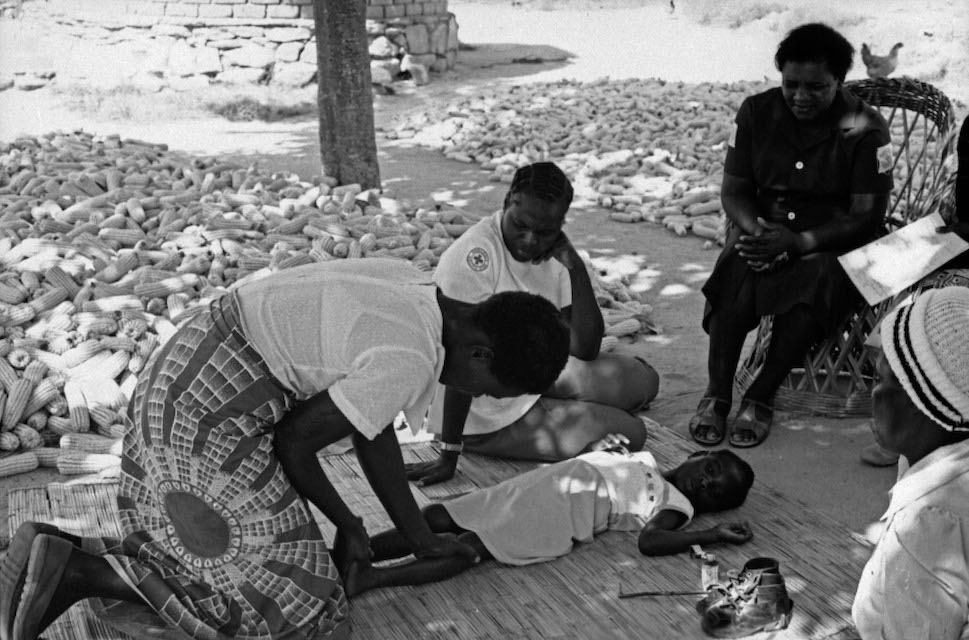

Thanks to the dedicated efforts of health workers, traditional and religious leaders, parents, Rotarians and country leaders, African nations have immunized hundreds of millions of children with polio vaccines, strengthened polio surveillance networks to detect any lingering traces of the virus, and implemented strategies to immunize hard-to-reach children.

In 2020, a significant milestone is expected for polio eradication and global health: the certification of the WHO African Region as free of wild poliovirus. In 2019, Nigeria, last polio-endemic country in Africa,

Once the WHO African region is certified to have eradicated wild poliovirus, five of the six WHO regions, representing over 90% of the world’s population – would be free of the wild poliovirus.

Today, the fight continues against all forms of poliovirus. A rare vaccine-derived version of the poliovirus is affecting African countries with low immunization coverage, particularly among remote communities and those experiencing migration or conflict. Renewed efforts are underway to rid Africa of all remaining vaccine-derived polioviruses.

Over the years, the polio eradication program in the African Region has developed the technical expertise, disease surveillance and community networks and logistics capacity to respond to other diseases, and is often the first response to disease outbreaks, including the Ebola outbreaks in West Africa (2014) and DRC (2019).

In 2020, the polio eradication program adjusted to address the COVID-19 pandemic sweeping across the globe, with polio vaccination activities

Challenges

In 2020, a significant milestone is expected for polio eradication and global health: the certification of the WHO African region as free wild poliovirus (WPV). This remarkable success is thanks to the mass immunization of millions of children using the oral polio vaccine (OPV). However, a rare strain of circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs) affecting under-immunized communities still needs to be addressed.

Circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs)

OPV is a very safe and effective vaccine. The global incidence of polio has reduced by more than >99% since 1988, with more than 10 billion doses of OPV have been given to more than 2.5 billion children in the last ten years. OPV also prevents person to person transmission of the virus. Once someone has taken the oral vaccine, the weakened virus is excreted out for a few weeks afterwards. In places with poor sanitation, others may consume food or water contaminated with this weakened virus in a process that acts like passive vaccination.

However, if a population is seriously under-immunized, the excreted vaccine-virus begins circulating among susceptible children in the community. If the virus is able to circulate for a prolonged period of time uninterrupted, it can mutate and over time can become virulent. This is known as a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

cVDPVs in the African Region

A number of countries in the African region continue to experience cVDPVs, for which outbreak response campaigns are conducted.

These countries—many of which share borders—face similar challenges including low routine vaccination coverage, vaccine refusal among certain communities, difficult access to some locations, regional migration and displacement patterns and variations in the quality of vaccination campaigns. As a result, many thousands of children are left unprotected from polio and other vaccine-preventable childhood diseases.

Responding to cVDPVs

To address the growing challenge of cVDPVs, the GPEI’s new ‘Strategy for the Response to Type 2 Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus 2020-2021’ is focused on working with affected and at-risk countries to control cVDPV outbreaks ongoing across the African Region.

The first stage of this targeted strategy involved launching a rapid response team (RRT) specifically to respond to cVDPVs. Formed in September 2019, the team is coordinated from WHO’s Regional Office for Africa in Brazzaville and is composed of twenty experts in operations and vaccination management, epidemiology, logistics, and communications, drawn from GPEI’s core partners.

With polio targeted for eradication, even one case is an outbreak which requires immediate action. Every time a new polio outbreak is confirmed or even suspected in the African Region, the team is dispatched to the country within 72 hours. They quickly get to work putting together the building blocks in place for a 6-month outbreak response. Outbreaks are usually rapidly stopped with 2 to 3 rounds of high quality supplementary immunization activities.

If there are no outbreaks, the RRT focuses on preparedness planning from its base in Brazzaville. There are also 'virtual' global polio outbreak preparedness and rapid response teams (OPRRT) based at WHO's headquarters in Geneva, UNICEF headquarters in New York, and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta on stand-by if needed, supporting outbreaks in other WHO regions.

The second stage of the GPEI strategy involves the roll out of a new vaccine, called novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV). This is a stable version of the type 2 oral polio vaccine, which clinical trials have shown is safe and effective in protecting against type 2 polio viruses but also less likely than the current OPV to revert into a form of the virus that causes paralysis. At the end of 2020, nOPV is planned for global roll out upon agreement with national regulatory authorities.

The third stage is focused on strengthening routine immunization, both with the oral polio vaccine, and, particularly in areas at risk of cVDPVs, with the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). Maintaining high collective immunity through routine immunization remains the backbone of any eradication program. In order to prevent importations of polio virus and protect as many children as possible, African countries should continue to use both the OPV and the IPV, that will ensure that both wild poliovirus and cVDPVs are kept at bay.

WHO Response

In 1988, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution to eradicate polio by the year 2000. Then, polio was endemic in 125 countries across five continents and paralysed 1000 children every day, some 350,000 children every year. Such an ambitious task required a mobilisation of efforts that cut across borders and institutions. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched, the largest public health initiative the world has ever known, with the common purpose of vaccinating children in every corner of the globe against polio.

Today, the GPEI partnership includes WHO, Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance along with national governments. The GPEI’s work is organised through the WHO Regional Offices in Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, The Western Pacific, South-East Asia, Europe and the Americas. The partnership is financed by a wide range of public and private donors. Between 1988 and 2018, over US$16 billion dollars has been provided by over 100 public and private sector donors.

Through this partnership, the polio programme vaccinates around 400 million children every year. More than 20 million mostly female volunteers around the world, who coordinate the delivery of polio vaccines as well as other basic healthcare to the people who need it most, make this possible.

Overall, since the GPEI was launched, the number of cases globally has fallen by over 99%. More than 18 million people are able to walk today, who would otherwise have been paralysed. Four out of five people in the world now live in certified polio-free regions, and the polio program is continuously learning and adapting to overcome challenges to eradicate polio once and for all. WPV3 was declared as globally eradicated in 2019, while WPV2 was declared as globally eradicated in 2015. As for WPV1 it is currently endemic in only two countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan. Africa's last detected WPV1 transmission was detected in Nigeria in August 2016.

Polio in the African Region

The African Region has made monumental efforts towards eradicating polio over many years. In 1996, the Kick Polio out of Africa campaign, launched by then South African President Nelson Mandela helped transform the political commitment of the ‘Yaoundé Declaration’ to eradicate polio from Africa into a popular movement. At the time it was estimated that 75,000 children in Africa were paralysed each year from polio.

Since then, political leaders, traditional and religious leaders, public health experts, partners, donors and communities united around eradicating polio from the continent. Hundreds of millions of children have been vaccinated, some in the most hard-to-reach, insecure parts of Africa.

Success has been hard won, with repeated outbreaks in Nigeria, Angola and DRC affecting the rest of the Region. However the African Region made strong progress under the GPEI Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018, towards certification of the African Region as free of wild poliovirus.

In August 2019, Nigeria marked three years since last reporting a case of wild poliovirus. By March 2020, over 43 countries in the African Region have had their documentation accepted after undergoing a rigorous certification process by an independent group of experts called the African Regional Certification Commission for wild poliomyelitis eradication (ARCC). The WHO African Region is on track to be certified free of wild polio virus in 2020.

However, challenges remain in Africa with weak health systems and multiple competing health priorities, and poor immunization coverage among remote communities or those experiencing migration or conflict, along with growing population densities and poor sanitation in cities. A rare vaccine-derived version of the virus persists, which has been seen across 15 African countries since 2017. This raises concerns that the virus could emerge again.

Polio Endgame Strategy

To bring the world closer to the global eradication of polio, the GPEI created the GPEI Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023 which ramps up the strategies that caused the 99% drop in polio cases since 1988, and implements new and innovative tactics to ensure every last child is protected with the polio vaccine. The Endgame Strategy lays out three main pillars for achieving a world free of all polio viruses: Eradication (through immunization and disease surveillance), Integration and Containment.

More so than previous GPEI plans, the Endgame strategy targets the increasing number of circulating vaccine-derived polio viruses. It now includes a roadmap for responding to type 2 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus, unrolled over 2020 and 2021, laying out new tools such as the use of a new vaccine, the novel OPV (nOPV) as well as other assets to improve outbreak response.

In 2019, the Polio Oversight Board (POB) approved a multi-year budget to implement the strategy of $4.2 billion. At the Reaching the Last Mile Forum in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, global leaders and philanthropists pledged a total of $2.6 billion. The strategy’s ultimate success in bringing about a world free of polio, however, depends on full implementation, which in turn can only happen with full financing and complete political commitment.

The Last Mile

While the number of polio cases has fallen globally by 99%, reaching the final 1% is proving to be the toughest phase of polio eradication. Yet with sufficient resources, country-level commitment, and access to hard-to-reach areas, polio transmission can be ended. Once three years have passed without any transmission of WPV1, the last remaining wild poliovirus type, wild poliovirus will be eligible to be certified as eradicated globally. This will be followed by the global cessation of OPV use and a separate, independent process to validate the absence of vaccine-derived polio. All stakeholders must remain committed to continuing vaccination campaigns until this disease is eradicated for good.

Post-certification

The eradication of wild poliovirus will be a major milestone in human history. To protect this accomplishment and maintain a polio-free world, the world will transition fully to the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which will eliminate the risk of vaccine-derived polio. Even when wild poliovirus is eradicated, the WHO will continue certain essential functions for a period of time – including routine vaccination, disease surveillance and outbreak response capacities, and containment of existing polioviruses in laboratories and vaccine production facilities.

Transition of Resources

The tools, infrastructure and knowledge developed to eradicate polio have saved countless lives across the globe. They’ve been used to fight many vaccine-preventable childhood diseases, tackle disease outbreaks including yellow fever, meningitis, Ebola and COVID-19, deliver malaria prevention tools, register more births, and improve disease surveillance worldwide. The GPEI is working with 16 priority countries in Africa on transition planning – integrating polio staff, resources and functions into essential health-care services including vaccination to ensure sustainable health systems.

In many fragile and conflict-affected states, including immunization, surveillance, laboratory services, response, and risk communication is essential to keep the world safe from epidemics and other health emergencies.

Disease

The virus

Poliomyelitis, or polio for short, is a highly infectious viral disease. The virus, which mainly affects children under five, attacks the brain and spinal cord and can cause total paralysis within days of infection. There are three poliovirus serotypes, Type 1, 2 and 3 all of which have identical symptoms, for which there is no cure.

The virus is transmitted person-to-person mainly through the faecal-oral route, or less frequently through a common vehicle for example food or water that is contaminated with the virus. Once the virus has entered the body, usually through the mouth, it multiplies in the throat and intestines, and can also enter the bloodstream and spread to the nervous system. Although children are more likely to catch polio, adults - who often carry the virus without displaying symptoms - help to spread it. Environmental factors including poor sanitation can also help spread the virus.

Symptoms and diagnosis

The majority of people the virus infects do not show any signs of infection, though some experience symptoms, which include sudden onset of fever, tiredness, headache, vomiting, stiffness of the neck, aching muscles and pain in the limbs. In a smaller number of cases, the virus invades the central nervous system, causing paralysis, usually in the legs and sometimes in the arms. For many, this is only temporary, and the sufferer regains movement over time, usually within weeks or months. For others, however, the paralysis—known as acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) - is irreversible. In rare cases this results in death when the breathing muscles become immobilised. Around one in 200 suffer permanent paralysis, and five to ten percent among those paralysed die.

For the majority who survive there can still be life-long complications. Sufferers may have permanent deformities, such as twisted legs or feet, weakness or shrinking of the muscles, or tight joints. Some experience post-polio syndrome: a poorly understood condition that sees symptoms return years after the sufferer recovered from the infection and that affects even those who had no symptoms at the time that they had polio.

Polio vaccines

The development of vaccines for polio was one of the major breakthroughs of the twentieth century. The first effective injectable polio vaccine was produced in Pittsburgh in 1955 by Dr Jonas Salk, following which the United States launched the first mass immunization campaigns. An oral vaccine, developed by Dr Albert Sabin came onto the market in 1961. With these two life-saving innovations, eradication became possible.

There are two types of vaccines used to stop the spread of polio. The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is injected, contains deactivated viruses and creates antibodies in the blood. Used in industrialised, polio-free countries, it has a few drawbacks, namely that while the vaccinated person is protected from the disease, if the virus enters their gut it can still be passed on to others through the oral-faecal route for several weeks after the vaccination is administered. It is therefore less effective in high risk areas with lower levels of vaccination in the community.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) contains the weakened live virus and creates antibodies in the gut rather than the blood. Given in two doses during routine immunization and three doses during supplementary immunization activities delivered up to a month apart, OPV provides lifelong immunity to polio. As such, even if the vaccinated person consumes food or water contaminated with polio virus in the few weeks after it is administered, the vaccine antibodies in the gut fight the wild poliovirus when it enters through digestion. This means that the OPV not only protects the individual child, but also offers more protection to the community than the IPV.

OPV is also more suited to low-resource settings: unlike the IPV, it does not require expensive sterilized syringes nor special skills to administer it, so immunization campaigns can easily be rolled out by volunteers with minimal training.

When enough people in a community are immunized against polio, the virus is deprived of susceptible hosts and dies out. At least 90% of children should be fully vaccinated to make sure that the disease doesn't spread among the population if it is reintroduced, as just one infected child can start an outbreak.

Eradication

Polio Eradication

Eradicating a disease requires a comprehensive, long-term strategy with rigorous methods that measure success. To achieve the global certification of polio eradication, the GPEI Polio Endgame Strategy 2019-2023 lays out three main pillars for achieving a world free of all polioviruses: Eradication (through immunization and disease surveillance), Integration and Containment. This strategy builds on the GPEI Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018 under which the African Region has made strong progress towards certification.

ERADICATION

1. Immunization

Routine Immunization The backbone of polio eradication is achieving high vaccination coverage among children. The best way to realize this is to add the oral polio vaccine (OPV), given in three doses to national routine immunization schedules. This level of coverage must be maintained, even after countries are declared polio free, because the virus can be re-introduced by cross-border travel and hesitancy around the vaccine.

Supplementary immunization

Supplementary immunization does not replace routine immunization but catches children who, for various reasons, have been missed and are either not immunized or only partially immunized. It also boosts the immunity of children who have already received the full vaccination.

Supplementary immunization is often done through national immunization days (NIDs) which target every child under the age of five. Each child, regardless of their immunization status, gets two doses of the oral polio vaccine usually given one month apart. Vaccinating a whole targeted age group in one go is particularly impactful in disrupting the spread of the disease.

NIDs are run by volunteers who, thanks to the simplicity of the oral polio vaccine, are able to serve as vaccinators after basic training. In the Africa region, supplemental activities also allow for additional primary health activities, including measles vaccinations or delivery of deworming tablets and vitamin A doses.

Targeted mop-up campaigns

Even with routine vaccination and supplementary immunization some children are still left un- or under-protected. To reach these remaining children, volunteers go door-to-door to administer the vaccine, in what are known as mop-up campaigns. In particular, these campaigns target itinerant or nomadic communities, which are often resistant to vaccination, as well as people living in areas with high population density, poor sanitation, and low routine immunization coverage. Mop-up campaigns also focus on places where the virus has been identified within the last three years, or where there are other indications that it may be circulating.

Disease Surveillance

Active surveillance is central to the whole polio eradication initiative. Across the African Region a network of dedicated laboratories, virologists and field surveillance staff at each level play a role in the chain of surveillance.

Health workers in health facilities, from district health centers in rural areas to large city hospitals, are trained to recognize and report every case presenting with sudden weakness of limbs technically known as acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), associated with polio, in any child under the age of 15.

National health staff also make routine visits to healthcare facilities, including hospitals and rehabilitation centers, to look for children with AFP who have not been identified or who have been misdiagnosed. In many parts of the African Region, the lack of health facilities and healthcare workers has meant training key members of the community including religious leaders, traditional healers and pharmacists to conduct community surveillance.

Once a case of AFP has been reported, two stool samples are collected from the AFP patient, 24 hours and 48 hours apart, ideally within 14 days of the onset of paralysis, and transported to the nearest dedicated laboratory. Results must be reported within 28 days, allowing countries to take action immediately to limit virus spread.

Over the years, polio testing has developed more sophisticated analysis to provide quicker results for response measures. Today, laboratories are able to determine the genetic make-up of the virus in each case, whether it is a wild or vaccine-derived polio strain, and, from this, identify the geographic origin of the particular strain. This information then allows for targeted vaccination campaigns to prevent disease spread.

More recently, environmental surveillance – which entails collecting and testing sewerage samples that may contain polio viruses in human faeces – is being used to complement surveillance and provide an early warning of circulating viruses in the area, even when there are no reported cases of paralysis.

Integration

Over the years, the polio eradication programme has developed extensive tools, infrastructure, knowledge and best practices in immunization, disease surveillance and outbreak response, as well as a vast network of human resources and wide geographic access. Polio resources have contributed tremendously to responding to humanitarian emergencies and diseases outbreaks across the African region.

Beyond polio eradication, these are being directed towards supporting and strengthening Africa’s health systems more broadly, including integrated disease surveillance and public health responses to a broader range of vaccine-preventable or epidemic-prone diseases, including measles, yellow fever, meningitis, cholera and more recently Ebola and COVID-19. Measles campaigns supported by polio infrastructure have resulted in a 50% decline in measles deaths since 2000, whilst the successful response to Ebola outbreak in Nigeria is partly attributed to the support offered by the polio programme.

In addition, the polio network is at the forefront of responding to humanitarian emergencies, including natural and man-made disasters, having contributed to efforts to relieve droughts in the Horn of Africa and in the Sahel.

Certification and containment

In order to certify the African Region as free of wild polio, a formal standardized process of certification is followed where all countries are required to meet strict criteria across immunization, disease surveillance and containment. All data collection and polio eradication activities are assessed by an independent body called the Africa Regional Certification Commission (ARCC). A region is certified as wild polio free after meeting all the criteria for certification and after three years have passed without detection of any wild poliovirus in any country in the region.

Containment includes the destruction of polioviruses in laboratories, biosafety and biosecurity requirements for laboratories, vaccine production sites, or any other facility that handles or stores eradicated polioviruses, to minimize the risk of polio viruses being released into the community that may result in the reintroduction of the virus and cause outbreaks.

Polio support to the Covid-19 response

In March 2020, as a localised COVID-19 outbreak evolved into a global pandemic, the GPEI POB took decisive action to repurpose the polio eradication program’s staff, assets and funding to contribute towards the global COVID-19 response, while maintaining critical functions including disease surveillance and planning for a full resumption of polio eradication activities once the situation stabilizes.

In the African Region, the polio eradication program – with its technical expertise, disease surveillance and community networks and logistics capacity – has long overseen responses to other vaccine preventable diseases and are often the first to respond to disease outbreaks. The program is now directing 60 to 70% of its combined resources towards the COVID-19 response.

The GPEI’s updated strategy has called for a resilient, flexible approach to polio planning in 2020 and 2021 and polio operations will resume in intensified mode as soon as the COVID-19 situation safely allows. However, the program will face increased funding needs due to the pause in vaccination campaigns and slowdown in surveillance activities, as well as increased infection and prevention measures that will now be required for campaigns.